Looking at the Future

A wide-ranging conversation with Ramez Naam: Futurist, author, and investor.

👋 Hello to 3,164 climate buddies 🌳

Delphi Zero explores the interplay of climate, energy, and security 🌳🔋🛡️

📧 If you are opening this essay in your email inbox, I recommend clicking on the title of this piece to enjoy the full-length version in the browser.

Today’s interview is a very special one. Let me explain.

Since starting this publication back in 2022, Ramez (Mez) Naam was at the very top of my list of “people I’d love to interview one day.”

Not only did he predict the growth of solar more than a decade ago but he’s also an accomplished Sci-Fi author. I still have a vivid memory reading his Nexus book series on a rush-hour train ride from San Francisco to Fremont. While clinging onto the handrail myself, the main characters of the story were attending a neuro-hacking warehouse party in Oakland - a few miles from where exactly I was in that moment. It was a surreal feeling.

Fast forward to 2022, when diving head-first into the energy and climate space, I read his long-form interview on the Noah Smith newsletter. It was tremendously helpful to get an updated high-level view of the world (anno 2022). It might have been one of the reasons why I went back to uni to study Energy Law. I still recommend it to friends who want to learn more about the space. (You should also read it)

With this interview, I’m coming full circle to all the topics that set me on my own climate journey:

Frontier technologies that are indistinguishable from magic

Stories of possible futures we’d like to live in

And last but not least, the realities of the human condition as part of this equation

We discussed this and much much more.

Enjoy ✌️

Looking at the Future

By Art Lapinsch

Mez, thanks for doing this. This is very exciting. Let's dive right in. What role do you believe (science) fiction plays in driving human progress? Why?

I think there are a number of roles that science fiction has played and continues to play.

It's definitely been an inspiration for many kids and teens that eventually led to them working in the sciences or technical fields. I meet people all the time who went into engineering, or software, or the sciences because they were fascinated by and inspired by science fiction they read in their youth.

There's also a role of science fiction in encouraging scientists and engineers along certain research and product paths. The story of how Star Trek communicators influenced the design of flip phones is well known.

I've been incredibly flattered at times when neuroscientists or neurotech entrepreneurs tell me that they want to build the Nexus brain technology in my books. Though this is also a bit of a feedback loop. In several of those cases I've said to them, "I was reading your papers when researching the novel!"

The real advantage science fiction has here is being unmoored from the timelines of shipping products, publishing papers, or securing grants.

Science fiction authors can simply look much further out - and talk about it publicly - than mainstream scientists. This became really clear to me when the head of a large neuroscience institute invited me to come speak to the assembled scientists there. I would obviously be the least qualified person in the room. I'm not a neuroscientist! I said this, and the institute head told me, "Yes, but I can't get my scientists to look beyond their next grant! I want you to challenge them about what we could do in 50 years or 100 years."

Well, even there, I probably know less than any of the scientists, but as a fiction author, you have license to dream.

All of that said, I think the even bigger impact of science fiction in driving human progress is in writing about future paths of civilization, either optimistically or pessimistically. Science fiction is often chock full of social commentary. It's often about anxieties of the present and what that could mean for the future.

Sometimes that manifests in deeply utopian work that can inspire people towards building a better future. Star Trek fits that bill. It's a post-scarcity, egalitarian society. On the other hand, sometimes it manifests as dark warning tales about the future, driven by the present.

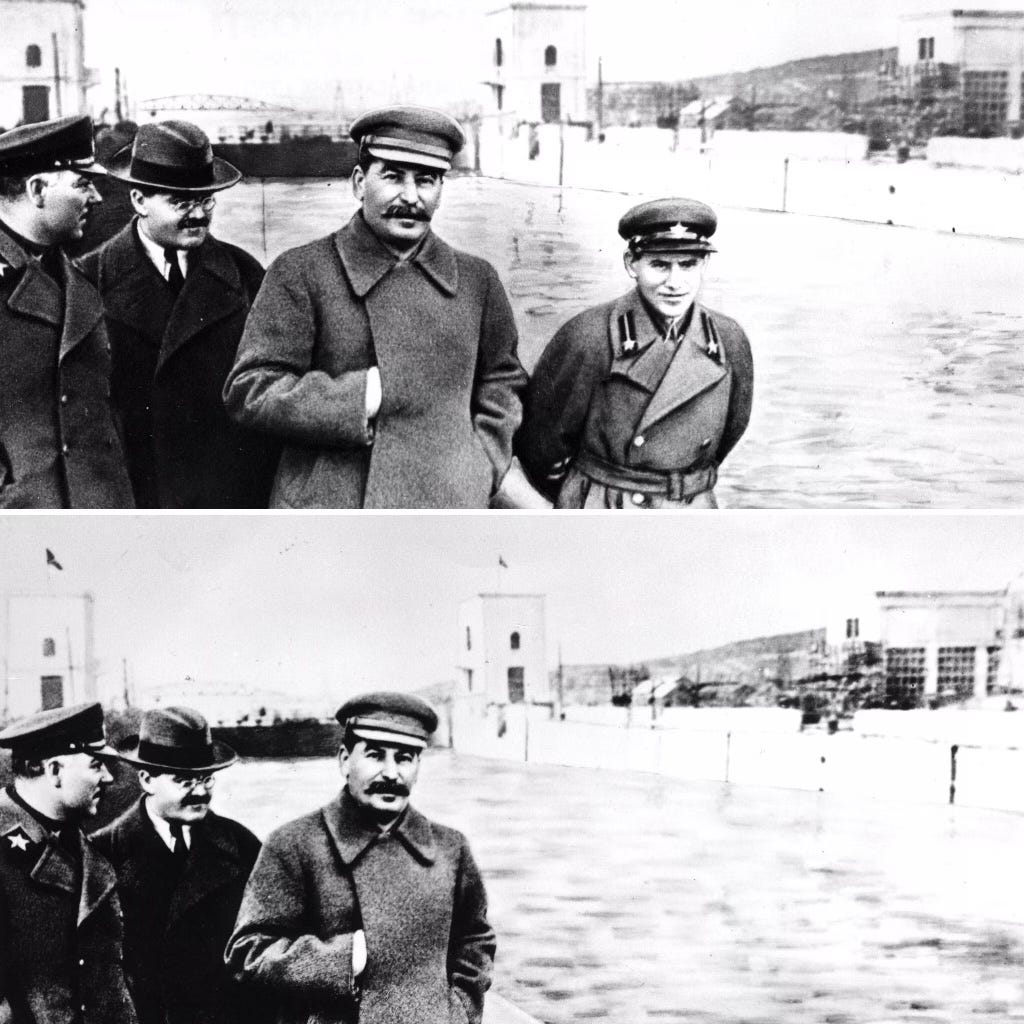

Orwell wrote 1984 in 1948 (see what he did there?) and what the novel was at least part driven by his horror at what he saw Stalin doing in the USSR. Stalin was erasing people from history. There's a famous photo of Stalin and three other leaders of the USSR. One by one, as those men fell out of Stalin's favor, Stalin had them executed. And each time, he had a new version of the photo reduced with that person edited out (long before PhotoShop or AI editing tools!)

Stalin did this sort of thing with many famous photos, actually. And so Orwell saw a future where the state, under a dictatorial rule, actively used the media to gaslight the populace.

Now, many people have said over the years "science fiction ought to be more optimistic!" But both of these types of social commentary have their role. The inspirational future of Star Trek can inspire, and also cast a lens on topics like racism. And the dark stories like 1984, if they're well done and relevant, can become what David Brin has called "self-defeating prophecies", where they inoculate society against potential failure modes in the future.

Personally, I think both are important, and I try to weave both elements into my novels, at the same time.

Before we dive deeper into technology, I have to ask about your writing process. Can you share why and how you wrote the Nexus trilogy? Was there anything particularly surprising about the process?

Nexus was born out of a fascination I had with neuroscience plus my frustration with the War on Drugs and the War on Terror.

I'd written a non-fiction book long before then, More Than Human, that looked at the science and ethics of human enhancement. Could we turn humans into superhumans? Should we? And as I researched and wrote that book, the technology that fascinated me most was neurotech, and specifically the emerging field of brain-computer interfaces.

At some point several years later, some friends who were fellow sci-fi buffs suggested forming a little science fiction writing circle. We all worked on short stories and shared them with each other. I decided my story would riff off of those brain computer interface technologies and imagine a world where they were really mature and had really low barriers to usage.

I didn't expect to ever do anything with that story, but sometime later, I quit my job in tech, intending to write a non-fiction book on climate and energy. That book, The Infinite Resource, eventually came out just a few months after Nexus, but for a while it was stalled. So, with no job, my main project stalled, I decided to try my hand at turning the short story I'd written into a novel.

The technology and my fascination with the brain in general were one impetus. Burning man culture, which I've been a part of for decades now, was another. But what motivated the plot was really a philosophical debate about who gets to decide what you put into your brain. What civil rights do we have? Do we own our own bodies and brains? Can we make informed decisions about them?

I've long been appalled by the so-called War on Drugs. Drugs have some real negative effects on society, but the War on Drugs makes all of them worse, and tramples civil rights along the way. I was also writing in the years after 9/11 and the War on Terror, which I also felt was really trampling civil liberties, and could lead us to a world of a more powerful state that really restricted individual behavior in ways beyond those needed for a decent level of safety.

So I threw all those ingredients together, along with what I saw happening in the wider world geopolitically - China's rise, a coming cold war between the US and China, and so on - into one book (later a trilogy), and then just tried to make it as mind-blowing and tightly paced and plotted as I could.

One of the main questions I've been asking myself is "Where is Top Gun for Climate?" Can you think of a fiction story that does a good job of covering climate? As a writer, do you think there are particular challenges or opportunities when writing climate-related stories?

There's plenty of climate fiction out there.

Kim Stanley Robinson's Ministry for the Future is the most visible recent example. Paolo Bacigalupi's novels all touch on climate change, for example, The Water Knife. Tobias' Buckell's Arctic Rising is another.

Most climate fiction uses climate change as part of the world building and context. It's just generally something that has affected the world that the characters live in. Stan Robinson is the exception to this, where his work really deals with how to address climate change.

Personally, I like to write about dealing with big problems, but I find climate difficult to frame as the main problem of a novel, because the timeframes for solutions are just so long.

The Nexus trilogy takes place over the timeframe of a few years. That's long enough for a technological revolution to start, and social implications to be felt. But it's not the timeframe of decades or perhaps even a century that the fight against climate change will span. That timeframe just makes it difficult to make a fight against climate the centerpoint of a novel, unless you're writing a multi-generational novel, which is very different than my style or that of most authors.

That said, it's hard to write a plausible future set in the next century on earth where climate change isn't one of the major background elements of the world. William Gibson did this in a sort of indirect way in The Peripheral. The novel isn't about climate change, but one of the background elements is "The Jackpot" - a poly-crisis that humanity goes through in his timeline that causes severe environmental and economic disruption. Gibson doesn't dwell on this - it's just part of the world the characters live with. And I think that's the most realistic way to deal with it.

One thing I do think is important, though, is showing some degree of hope. As someone whose day job is climate and energy, I do think we will round the corner on this, and that the most likely outcome is that, a century from now, while there will be scars from climate change, the median person on earth will be far better off than they are today.

So something I'd like to see more of in fiction is stories where, yes, climate change is real, and did real damage, but society came through it, found solutions, and has actually grown more prosperous, and is perhaps even changed in positive ways by the experience of having to overcome climate and other challenges. I think there's room for many more stories of that sort.

Let's dig into your day job. Before reading your novels, I knew you as the guy who had an overly-optimistic (at least according to IEA/etc. consensus) view on solar PV learning rates. In hindsight, you were more right than others. How did you spot these trends and why do you think others have missed them repeatedly?

It is the other thing I'm known for.

Back in 2010, the IEA was predicting that the cost of solar would drop roughly in half by 2050. I wrote a piece for Scientific American where I looked at the last decade of cost declines and predicted that costs would drop by more than a factor of 10. I was called a crazy optimist. And I was in fact wrong - costs have actually dropped about twice as fast as I predicted.

How did I get that right? I credit coming from tech and futurism. My degree is in computer science. I'd worked 15 years in tech at that point, and seen the incredible power of Moore's Law. I'd read Kurzweil, and gotten to know him some, and seen exponentials in a lot of fields. So when I was working on my book asking if we could innovate our way out of resource challenges, environmental challenges, population growth, and so on, one of the first things I did was look at trends in clean energy technologies. I downloaded some data on the cost of solar from NREL (the National Renewable Energy Lab). I put it in a spreadsheet, and, as is my norm, I changed the Y axis to a log scale. Honestly, anyone doing data analysis should use log scales for the vertical axis more often. If it's a dataset that contains any exponential component - even a slow exponential like the stock market or GDP - a log Y axis is just so much more revealing.

Well, on this log scale, the cost of solar was dropping, and it was pretty much a straight line. That's exactly what you see in the cost of computing - Moore's Law - or in related costs of bandwidth, memory, storage, etc...

I'll be honest, at that point I knew just enough about energy to be dangerous. There were so many things I didn't understand about the complexities of energy technologies or even energy costs and pricing. Simple things like the difference between the wholesale cost of generation (what's coming out of the powerplant) vs the cost for consumers (which includes the grid itself, which nearly doubles the cost).

Either way, that straight line on a log scale got me excited, and I boldly wrote that there appeared to be an exponential cost decline in solar. And that was correct. Not because I knew much about solar, but because a background in tech gave me this habit of looking for and thinking about exponential technology trends.

Since then I've learned a lot more. The way to look at these costs trends is really as a function of scale, not time. Industries learn as a function of scaling. And it turns out that there are scores of different technologies - in dozens of industries - that have these learning rates. But the rates are different from technology to technology, and increasingly we understand why and can predict which technologies will drop in cost the fastest, which is both awesome and pretty darn useful.

I remember reading your interview with Noah Smith back in 2022 - right after Russia's invasion of Ukraine. Back then, you made a qualitative prediction that Putin's invasion would accelerate the clean energy transition. What's your stock take in 2025? What did you get right and what did you miss? Why?

This was one of my more controversial predictions!

It's largely come to pass, though. In 2021, Europe had about 160GWs of solar installed. By end of 2024 they had more than 300GWs and on path to (conservatively) more than 600GWs by 2030. New policies mandate solar on essentially all new buildings in the EU. Heat pump deployment pace has roughly doubled in Europe (as so much natural gas is used for building heat).

The pace of battery deployments in Europe has grown nearly 10-fold from 2020 to 2024. 2023 set a record for European wind deployments. And offshore wind investments in particular have hit 30 billion euros a year, compared to less than a billion euros in 2022.

One thing that's particularly important is that the EU and some member states have moved to make permitting easier for renewables, and especially wind power, which gets hit the hardest by overly strict permitting rules. The EU has done this. And Germany and Poland in particular have made siting wind projects easier. There are more reforms at the EU level and member state level on the way.

What did I miss? I'd say I under-emphasized the importance of energy efficiency, across individual uses and economies as a whole. Germany in particular did an amazing job turning down the most inefficient uses of energy to focus on the most productive and valuable uses.

A mixed bag, I'd say, is what's happened in nuclear. It was frankly too late for Germany to alter its nuclear shutdown plans dramatically, which is really unfortunate, though there's now talk of possibly restarting some reactors in 2032.

Belgium, Sweden, the UK, and France are all moving forward with more reactors, and Poland is building their very first nuclear reactor, but this is all not at the scale or with the cookie-cutter approach that's likely necessary to really bring nuclear costs and construction times down. The invasion of Ukraine was an opportunity to get an ambitious nuclear power plan going in Europe, but it didn't happen.

And of course, the other big energy story is Europe's diversification of natural gas supply. There's only so fast you can replace the enormous amount of natural gas that Europe imports from Russia with renewables. In the short run, it's been easier to import LNG from the US and Qatar. Frankly, I'm fine with that. The Russian gas weapon over Europe needs to be eliminated. We'll eventually get rid of all of those emissions. But in the meantime we can't let Putin hold Europe over a barrel.

What if you'd have to give a prediction give the current state of geo-politics? Anything energy-, climate-, or security-related that stands out? What do you think most people are missing?

Geo-politics has certainly gone up in intensity in the past several weeks!

One clear trend to my view is that information technology is really disrupting defense and warfare and providing asymmetric benefits to the side with greater agency, smarts, and initiative.

The Ukraine-Russia war long ago turned into a drone war, with drones accounting for more than 75% of all casualties on the front lines. Their surprise attack against Russia's strategic bombers just showed the incredible power of these cheap software-controlled devices against hundred million dollar targets.

Israel's surprise attack on Iran showed the same. Battery powered drones aren't going to replace long distance weapons, but for a range of scenarios they're incredibly powerful, and that has to have every military planner on earth spinning their gears.

Right now, signal jamming is the number one defense against drones. But as we move into drones with onboard AI, machine vision that can follow terrain and identify targets, and even facial recognition, that defense goes away. As batteries and compute get smaller and lighter, the size of a killer drone will also drop, making them easier to conceal and sneak into places. I think this has pretty massive and maybe terrifying implications for any military target and also in civilian life. Compute continues to be on an exponential trend, and so is battery energy density, albeit a lower one. So this is a genie you can't easily put back in the bottle, and it's likely that defense is going to cost many many many times more than offense here for the foreseeable future.

What about energy? On a longer term, one of the best outcomes of electrifying transport is going to be the defunding of petrostates. The IEA just put out their latest forecast for peak global oil demand, which sees it coming around 2030. That's at the outside edge of the range I saw a decade ago, which was somewhere between 2025 and 2030.

The world won't change instantaneously when oil demand peaks. Oil consumption will probably stay on an undulating plateau for many years or a decade after that. But eventually we'll enter secular decline of the oil markets. And when that happens, while there will still be fluctuations in oil prices, they're going to start to decline. That takes funds away from some of the worst regimes on earth, including Russia and Iran.

Over time it'll reduce the strategic importance of the entire Middle East. That has lots of upside for the world. With the exception of Norway and the US, large oil-producing countries are not modern democracies. Even the ones that are our nominal allies - Saudi Arabia, for example - repress speech, execute people for criticizing their leaders or demanding rights, and have their own histories of sponsoring extremism.

Now, this transition isn't going to be all roses. The most positive outcome is that the coming decline of oil revenue spurs nations to modernize and to some extent liberalize. You can see this in Saudi Arabia, where MBS (Mohammed bin Salman) is trying to bring more women into the workforce and diversify their economy. But will it work? I doubt it will happen fast enough. Saudi Arabia runs a budget deficit at oil prices below $90/barrel. Finding new sources of economic productivity and shifting to them fast enough to make up for their existing deficit - not to mention the likelihood that it grows as we replace oil with EVs - is a very tall order.

So what happens when Russia, Saudi Arabia, Iran, and other nations no longer have that spigot of oil money? Obviously it reduces their ability to fund wars or extremist groups. But I think there's also a real risk of instability inside these countries as the money starts to dry up.

All that said, on balance, dropping oil consumption and dropping the bottom out of oil prices globally looks like a overwhelmingly positive thing for the world. It won't happen overnight, but it's going to happen.

And to some extent it's China, the largest battery manufacturer, largest EV manufacturer, and largest domestic market for EVs - that's leading the charge.

Alright, let's shift gears towards AI. What do you think most people over-appreciate and under-appreciate about this technology? Why? What's your current mental map for what's actually going on?

Can't we go back to easier topics like world peace? ;)

In all seriousness, AI is the most fascinating and possibly most bewildering subject out there right now.

First, I'd say that most people in the US and the world actually have minimal appreciation of what's possible with AI today. Only about half of Americans have even used an LLM. So the general public is mostly not engaged in this conversation. And when people do start to use it, they use it as either a better Google or as a kind of therapist/life coach. Both of which are awesome applications, but are probably just scratching the surface of what's actually possible. All up, I think the general public under-appreciates everything about AI as a technology.

AI is actually really profound, and I think the notion of "intelligence on demand" or "intelligence as a service" is mostly right, and that the general public doesn't understand that yet.

Almost all white collar work - from accounting to architecture - can be accelerated quite a bit by AI. I think we're headed for a surge of global creativity and innovation output, as almost anyone who wants to create, design, or analyze systems - whether they're words, numbers, images, or the design for a new car or home - will be super-powered.

People who have little to no skills in these areas will suddenly find themselves with some of those capabilities on tap. And experts will find themselves super-powered and accelerated, able to do things in a fraction of the time it usually took them, at larger scale, and often with new levels of quality or creativity or really substantial new innovations.

When I look at this, I see agency and curiosity as the new limiting factors. When intelligence (of a limited sort) is on tap for pennies, the thing that limits individuals and teams is going to be asking the right questions, having high enough aspirations for what we can accomplish, setting the right direction, and picking the problems to apply AI to. And the ability to exercise good judgment, to be skeptical of AI output to some degree, and to ride herd on these systems. The future belongs to the curious, the brave, and the motivated.

That said, I do think there are real unknowns and quite a bit of hype. Some of the unknowns are just how far AI techniques will go, and will AI systems truly be able to operate autonomously, or will they continue to require human supervision? I lean towards the latter for the foreseeable future.

AI systems are tools, but they really continue to require a human tool user in general. And while it's clear that in any narrow domain we can get AI to the level of the best humans or slightly better, it's not a slam dunk to me that we're on path to strongly superhuman systems. AI is dependent on the quality of its training data. And if you train an AI with data showing the very best of human thinking in a domain, it makes sense that an AI system can learn to match that, and even to exceed it somewhat, as no single human can truly stay abreast of the best work even in their single domain. But can current approaches lead to something that's 10x human quality in a domain? I honestly don't know. But it's far from proven yet. And I'm on the skeptical side.

Partially for that reason, I think there's too much hype in tech and AI circles about AGI (a vague term that confuses us quite a bit) and even more so about the idea of superintelligence. We can clearly build systems that are amazing at solving specific narrow problems, but they also go off the rails when you put them at the edge of their knowledge. And they require absolutely staggering amounts of training data - far more than a human does - and are running up against the limits of available training data. By some estimates in the next 3 or 4 years, frontier models will be training on nearly all publicly available human-created text. What happens after that? Where will the next improvements come from? How much can we improve them with synthetic data? If you're training AIs on data created by AIs, do we end up with a snake eating its tail?

Related to that, there's a lot of under-appreciation of how hard some of the problems people want to apply AI to - climate change, longevity, etc... - really are. There's some magical thinking going on that once we achieve AGI or SSI (if that's even achievable) suddenly we'll stop aging, or we'll make discoveries that allow us to beat climate change overnight.

For example, you have Demis Hassabis saying recently that AI could cure all diseases within 10 years. And Dario Amodei said recently that AI could double human lifespan in the next 5 years. Excuse me, but no. These are not serious statements.

I appreciate that Amodei and Hassabis are both trying to hype their companies, and the nature of tech and capitalism is that people make overly optimistic statements, but these are just dramatically off. AI almost certainly will help us accelerate biotech R&D. But these sorts of pronouncements are just ignoring the complexity of human biology - and of actually experimenting with biological systems - by orders of magnitude. I want to be clear that work like AlphaFold, that essentially solved the protein folding problem, is breathtakingly awesome. There are also orders of magnitude of complexity separating that from curing all diseases or doubling human lifespan. Knowing how each protein folds is great. Now, let's scale that up.

Inside of every human cell you have roughly 10 billion proteins, and large numbers of them are constantly interacting in complex and very non-linear networks. And your body has about a trillion cells. We simply lack the ability to model those interactions at scale, and LLMs in particular aren't going to solve that problem.

Biology is the most complex thing in the universe. It's code, but it's spaghetti code, and every change has ripple effects throughout the whole of the organism. That's even before you get into needing to run experiments, and then animal trials, and finally human trials to verify that what you expected to happen is what actually happens. Because usually, in biology, it's not that simple. Again, everything has side effects, many of them unexpected.

Similar things are true in other domains. A prominent AI person told me recently that AI would solve climate change. Just how do you see that happening? There's a physical world that requires physical R&D, prototypes, building factories, scaling to bring down cost, finding financing, finding customers, deploying in the real world. AI can help on the R&D side. One of my portfolio companies uses AI to help improve battery chemistries. But it doesn't magically solve the problem all at once.

Again, I don't want to downplay the benefits here. I truly believe that AI will accelerate R&D in biotech, in medicine, in chemistry, in materials science, in energy. Those applications of AI to improve our physical and biological technologies are some of the things that get me most excited. I think the potential value is huge. But it's not a panacea. We can't just hand wave problems and say "AGI will solve that".

I also see some downsides to AI. I'm overall extremely positive on AI. I think the societal value will be huge. But some scenarios concern me. In particular, I'm concerned about AI's effect on democracy. I was incredibly bullish on social media when it arrived. My Nexus novels make a case that increasing the ability of humans to communicate is fundamentally a huge positive for freedom and for society. Yet what I see now is that social media is often pretty toxic to public discourse and is being used as a weapon against democracy. AI could amplify that.

We have recent studies showing that LLM-based chatbots are more persuasive than humans when you unleash them on reddit or in structured debates. What happens when we have customized LLMs, trained on broad data but also on exact characteristics of a demographic, an audience, or even an individual target, and deployed as a tool of political persuasion? Using text and synthetic video and audio? Are we prepared for this world of hyper-persuasive, A/B tested, individually targeted manipulation bots? We could use AI to defend against that, of course. But do people even want to know the truth? Or do they prefer just getting content that aligns with their tribe and current beliefs? That scenario worries me far more than some superintelligence or dark singularity. It's right over the horizon.

So overall, I come down on the argument for "AI as a normal technology" as a recent paper argued. What I mean by that is that AI is actually totally amazing, and it's going to put incredible capabilities at the fingertips (or tip of the tongue) of billions of people around the world. I think it has huge implications for education, for all creative and design and engineering work, for accelerating the sciences, for mental health (when used constructively). And AI is going to pose real challenges. We should be worried about its use in manipulation. We should be worried about its effect on employment, even if it creates more new jobs than it destroys. It's a big deal. And at the same time, those "normal" impacts - pro and con - seem a lot more grounded to me than eschatological scenarios of recursive self-improving superintelligence that either saves or destroys the world. The hard work will come down to us and how we decide to use and regulate these tools, as both individuals and societies.

Mez, thank you so much for all your insights. I'd like to ask two last things: (1) Do you think all of the above will have a significant impact on the human condition? If yes, how? And (2) Where do you see us by 2050? Will we have achieved Net Zero or not? Why/how or Why/how not?

It's been a real pleasure, Art.

Regarding the human condition: Yeah, I think this does change the human condition, in ways that are both straightforward and that are harder to predict. The straightforward way is that we're heading for a world of more physical abundance and enhanced abilities to learn, analyze, and create. We're going to see new drugs, new progress in science and engineering, and a lower bar than ever to create art.

The harder to predict ways stem from how we interact with each other - as individuals and societies - and where we find the meaning of life. Will AI destroy jobs faster than it creates them? People have been predicting technological unemployment for almost a century now, and it hasn't really arrived yet. But maybe this time it's different. If it arrives, how will society deal with that? If we truly get to a place where very few humans can add economic value, how will we humans think about ourselves and our lives?

AI is also becoming a companion. We already have a trend where younger generations are doing more and more of their socialization electronically. Now what happens when more and more of your socialization is either mediated by AI or just interactions with AI? There are obvious good things here. AI will eventually make a great therapist. AI can help alleviate much of the loneliness and isolation of old age. But AI may also be more compelling to interact with than other humans for many people who are in the prime of their lives. We already see the rise of AI girlfriends and boyfriends, while the tech is still pretty primitive. I think we're heading for a world of hyper-romantic software, atop the hyper-persuasive capabilities I mentioned earlier. Porn already made depictions of sex unrealistic for a generation. Now AI will make depictions of romantic relationships - and maybe even friendships - unrealistic.

Ultimately the virtual world may just be more compelling than the real world. The science fiction author John Barnes has a concept that in the future, AI engineered to meet human desires leads to more and more humans going into "the box" - an immersive experience where they live whatever wonderful life they want through AI, rather than dealing with the messiness of the physical world. That's still science fiction and the technology to do that is still largely far out in the future, but little bits of it are getting closer. How will humanity deal with that?

All of that sounds pessimistic, but I'm still largely positive. The concrete benefits of more physical abundance, healthier lives, better science and engineering, and augmentation of our ability to think, learn, and create are just too large to ignore. I think we need to be aware of the risks, but not use that as an excuse to stifle the technology or all the many ways it can benefit us.

What do I see in 2050? Most likely, the world will be a better place. The median person on Earth will live in better health, with less burden of disease, less likelihood of hunger, more access to shelter and information and transportation and practical freedoms in their life. That's especially true in the developing world, where people's well being is rising faster than that in the already rich countries. But it's likely to be true almost everywhere on earth except for the countries with the very most dysfunctional governments. Crop yields will be up. Clean energy will be up. New medicines will be available. Education through cheap digital tools will be personalized and widely available. Language will increasingly recede as a barrier between people. Lots of good things.

Will we have stopped climate change? Will we have completely decarbonized the global energy system? I doubt it. There's just not enough time between now and 2050 to make that plausible. But we'll be on the other side of the peak. The peak of oil consumption will be in the rearview mirror. The peak of coal consumption will as well. Electricity generation and ground transport will be cleaner than ever, and dropping in the use of fossil fuels every year. We'll still be struggling with figuring out how to make the last 20 or 30% of electricity clean (especially in less-sunny place). We'll still have hundreds of millions of older gasoline and diesel powered cars and trucks on the road. And we'll still be using fossil fuels for a lot of heavy industry and for things like aviation. But the overall trajectory will be towards eliminating those emissions. And if we're lucky, we'll be able to see a path to actually hitting net zero in 2070 or 2080.

That's not a perfect world. There will increasingly be problems from climate change. There will still be people who go hungry. There will still be death and disease and poverty. But it'll be a world that's better than the one we live in now in the large majority of ways you can measure it, and where humanity increasingly has the tools to solve the problems that remain.

Thanks, Mez 🙏

I’d love to hear from you, please get in touch and tell me whom I should interview next or which topics you’d like to see covered ✌️