Clean Hustle

A chemist's sharp turn into the fierce world of hydrogen, policy, and climate cash.

👋 Hi to 1,521 climate buddies 🌳

Climate is not a technology problem but a story problem.

Delphi Zero is a consultancy and newsletter about the narrative potential of climate.

Today, I interviewed Gniewomir Flis.

He is mostly known for his spicy takes on the Hydrogen Economy and less so for being a proud ambassador of Polandcore 🇵🇱

He was one of the first people I met when entering this space as a total clown. Despite his stature, he was kind enough to listen, share his knowledge, and encourage my own climate journey. A total G. The streets will never forget!

I’m excited to share this wide-ranging conversation:

🧪 The transition from medicinal chemist to climate pro

⚗️ His work on the hydrogen economy with the legendary Michael Liebreich

🇪🇺 EU’s unexpected policy advantages over the US

💶 And various types of climate cash

I learned a ton and I am sure you will too!

Clean Hustle

By Art Lapinsch

How does a chemistry graduate end up in climate investing and consulting? What was your journey like? What were important inflection points and how did you maneuver them?

Chemistry is very fashionable and relevant to climate tech - both from the angle of understanding climate science, and also of various chemical pathways used to make and refine fuels, grow alternative proteins, or store energy.

So graduating in chemistry gave me a great technical background, albeit looking back if there was one thing I’d change, it's opting for an electrochemistry major, rather than a medicinal one. Electrochemistry is probably the hottest physical sciences field right now.

By the time I was nearing the end of my medicinal chemistry degree, I had no clue what I wanted to do, apart from not wanting to do medicinal chemistry.

Around the same time COP21 in Paris happened, and it seemed like a big deal. The science of climate change was clear to me since high school but it wasn’t until the Paris Agreement that I finally felt the world was getting serious on solving this issue. Now that we got an agreement, I became interested in contributing to solving this issue, because I figured real money will be flowing to this uncharted field.

Conveniently, Mirabelle Muuls from the Grantham Institute at Imperial College Business School had just finished designing a new degree around mobilising finance and organisational change for climate solutions. The degree - Masters in Climate Change, Management and Finance - was first offered in 2017. It seemed like a natural fit. I applied and got in for the pioneering cohort. Looking back, this was one of the best decisions I ever took.

At Imperial, I met Michael Liebreich who came in for a guest lecture. During the lecture he made a remark about posting a chart on Twitter around Heathrow’s runway expansion if anyone in the audience would do the digging for him. I came up to him after the lecture to volunteer looking into it. The first chart I produced for Michael was not Twitter worthy, but my analysis was apparently sound enough to hire me after I graduated.

After two years with Michael it was time for something different so I moved to Berlin to join Aurora Energy Research consulting arm. I was a pretty lousy team player back then so I got let go, but I was extremely lucky that another Berlin organisation - the think tank Agora Energiewende - was willing to take punt on me and my controversial hydrogen takes (more on that later!).

Agora was an overall great experience and it helped me develop as a team player and add new set of skills around policymaking and politics. I like to think of it in terms of hats. In first two years of my career, I wore a market analytics hat. Then at Agora, I switched to wearing a policy hat. Eventually, my controversial energy takes caught the attention of a newly formed venture fund in London. I got offered a role that would allow me to work with founders and technologies I’ve spent the last three years reading and writing about. It was a tough choice, because I also spent an entire year negotiating a Southeast Asian reassignment at Agora. But the fund offered thrice as much as Agora was paying. Man’s gotta eat.

In the venture space, networking is the name of the game. Now, as part of ’the club’ I quickly built up a network that highly valued my previous experience in market and techno-economic analytics combined with regulatory insights. I liked the freedom and the flexibility so I switched to offering freelance consulting services.

You are a well-respected expert on all-things hydrogen. How did you develop this expertise? What did you learn from working with Michael Liebreich?

My very first corporate job - one that I haven’t mentioned yet - was a 3 month stint as a summer analyst at Investec. There, I was tasked with producing a report fleshing out the ‘battle lines’ between hydrogen and competing technologies. This was during Summer 2017, just as the Hydrogen Council was being formed and the hype around hydrogen was beginning another cycle. So very early in my career I got to do a deep dive on hydrogen.

Next, at Liebreich Associates, in 2018 we started getting a lot of questions on hydrogen. I was tasked with looking deeper into it. Hilariously, we initially were suggesting hydrogen might be used in heating by highlighting peak gas demand vs. peak electricity demand in winter in the UK.

Around the same time, I made a Twitter account to anticipate what charts Michael would be sending me to make based on the replies to his posts. He sometimes would lend me his platform by retweeting or tagging me, helping build out a following.

When the 2019 IEA report on the Future of Hydrogen hit the web, I did my first twitter thread with key findings, which proved quite popular with the Twitter crowd.

People started reaching out to me directly, rather than through Liebreich Associates, to discuss hydrogen. They’d often ask questions I did not know the answer to, but I was determined to give them one. I started tracking this sector closely and on a day-to-day basis.

The easiest way to develop expertise, in my view, is to write about what you’ve learned publicly. It helps structure your thoughts, it builds up a network, and if you get something wrong, you can be sure an actual expert on the topic will come in and correct you on the internet.

Though, the writing must be engaging to attract an audience (or clickbait….)

For that, I have a lot to thank Michael for. His godlike storytelling leans a lot on exceptional data visualisation where the trend can be grasped by anyone within just three seconds. This principle is still the basis of a lot of the work I do today.

You don’t need to work for ML to learn at least some of his techniques though. Just read Edward Tufte’s “The Visual Display of Quantitative Information”. Life changing.

What’s your net-net on hydrogen? What’s over-hyped? What is under-appreciated? Why? What do you miss in the general discussion?

I think we’ve entered post hype-era, and we’re at the beginning of the Slope of Enlightenment, albeit this will vary geographically.

At least in the EU, we have almost finished hydrogen regulation, with the last remaining piece being negotiated in the trilogues, and have allocated meaningful public support to this nascent sector. I don’t think the support is excessive. If anything, I’d argue we should add more - probably a doubling on current levels - if we’re serious about our carbon neutrality objectives.

Some have argued that the US has leapfrogged the EU but I would disagree. In fact, they’re a little behind on hydrogen regulation, and it’s been entertaining to watch the Americans try to grapple with the same issues around supporting clean hydrogen that the EU spent two years on!

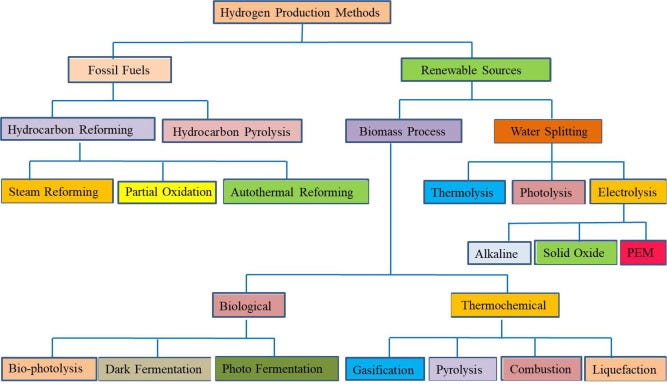

In terms of what’s overhyped, I would say water electrolysis. Incumbents are in a good position, but the dozens of startups will find it hard to compete with their industrial know-how accumulated over decades. Folks tend to underappreciate how much more similar electrolyser systems are to chemical plants than to solar panels, meaning they are more complex works of engineering.

For that matter, I also think that non-electrolytic hydrogen pathways are underrated.

Overall, I feel that the entire discussion around ‘hydrogen-economy’ is misguided.

There’s only a handful of uses where hydrogen has a clear cut case, and all are in the industrial sector. In my view, the starting point of the discussion should have been ‘industrial transformation’, of which hydrogen is only a subsection.

Let’s zoom out to the broader energy storage landscape. If you compare how European/US policymakers envision the future of energy storage with what is currently going on in the market (manufacturing; development; financing; etc.), where do you see the biggest disconnect? How can policymakers improve? How can the market improve?

The most obvious distinction is the approach towards leveling the playing field.

In the US, it’s by subsidising the supply of emerging technologies. Conversely, the EU has taken the approach of pricing in the externalities of dirty, incumbent technologies, making them more expensive. I think the latter improves, rather than distorts markets. In theory at least.

In practise, EU approach raises the costs to its industry, putting international competitiveness in jeopardy. The only way for EU industry to regain competitiveness for is to convince everyone else to price in carbon, which is one of the three key pillars of EU foreign policy.

Frankly, I think it’s the right thing to do, but it’s an uphill struggle. In the meanwhile, the EU does too little protect its own industry from asymmetric support foreign companies get from their home states. The proposed EU Sovereignty Fund which was meant to invest in European cleantech supply chains (but not only) on the back of common debt could have been a great remedy. Alas, that idea got shot down with member states left to fill the gap on their own.

What are the biggest regulatory opportunities that climate tech companies frequently overlook? Why are they frequently overlooked?

Grants.

There is usually a lot of money on the table, but the EU, and even member states, have grant opportunities stashed away across a byzantine network of programmes and funds. Yet these can be the difference between crossing the valley of death and not.

I would suggest reaching out to so-called National Contact Points, or alternatively specialised companies with deep knowledge of these funding ecosystems.

At risk of self-promotion, I am a consultant for one of such companies called Zaz Ventures.

What are the biggest struggles in your daily work? If you’d have a magic wand, how would you solve these obstacles?

Number one is just the sheer amount of work people come to me with.

Most of the time it’s interesting stuff and I find it hard to say no, and then have to work like a horse.

The other thing is original thought. When you are pushing the boundaries in a field, there are only a few people you can turn to when double checking your work.

You have worked in climate VC and have seen the clean tech bubble of 2021/22. What was going on? What have we learned? What will stay the same? Why?

I think it’s too early to say what we’ve learnt.

For sure, we’ve seen a massive influx of new capital from more conventional VC funds, but also the nouveau-tech-riche who are on a mission to save the planet. I still haven’t made up my mind whether it’s a net benefit or not.

On one hand, more money means better funded startups, which attracts more talent and gives more runway. On the other hand, I’ve seen stupid valuations at early stages that will make it hard for companies to raise money later, and some fundamentally flawed ideas getting funded after a single call with the founder.

I’m not old enough to remember the Cleantech 1.0 bubble, but I’ve heard stories of the ensuing cleantech winter when disillusioned investors wouldn’t touch the sector for over a decade.

Still, perhaps this time it really is different. Despite the obvious bubble which has popped (cleantech VC investment down by around 50% this year I believe), many companies this time around are led by scientists.

As a capital allocator in climate, what do you usually look at when making an investment decision? Why specifically those factors?

Team, market fit, tech. In that order.

A strong team will make an even mediocre technology work if they find a market fit. Then they can iterate and improve. But even the best technology will struggle to scale if the team fails to develop a successful business model.

What are some poorly-understood risk factors to reaching net zero? Why are they poorly understood? What’s your best guess on how to address those risk factors?

Populist backlash in the form of fossil-fuel loving, climate-change denying alt-right.

If Trump wins the next elections, I can’t imagine the damage he will do. I’m slightly less afraid of the next elections to the European Parliament, but ‘it remains an ongoing concern’ that keeps me up at night.

I don’t have an obvious answer how to address these risk factors, but I think we need to get better at communicating the benefits of the Union or policies like the IRA.

At least in the EU, the institutions are way too shy of flaunting their achievements left, right and centre, through any means necessary. In my view, that leaves the space almost wholly uncontested to the info wars types.

In terms of technology, where are we lagging behind? Where should we do more research? Why?

I don’t think the EU is lagging behind on any technology R&D.

Deployment seems to be a bigger problem. However, we are many years ahead on plastics and circularity, especially compared with the US. That’s where I’d like to see more research, deployment, and policy work, so that we can keep the advantage.

I believe material efficiency will become ever more important going forward. Secondary materials are typically a magnitude less carbon intensive than virgin materials. They also have far less impact on natural habitats.

What is something that you have changed your mind about since working in the climate space? What is something you have doubled down on?

I used to think 100% renewable energy systems were the logical consequence of experience curves.

Nowadays, I am an ardent supporter of a diverse mix that includes nuclear too. It’s a key technology for resilience, but also for industrial leadership beyond 2050.

In terms of doubling down - batteries. You ain’t seen nothing yet!

What is the most valuable idea you teach climate people on a regular basis? Why is it so little understood? Why is it valuable?

I mentioned this before but it bears repeating: You want to become an expert at something? Blog about it.

Helps to structure your thoughts and build a network. Clarity of thought, communications skills, and a network will take you far.

This is especially important for scientists who ought to unlearn the dry and almost robotic language of scientific writing.

Sometimes great innovation doesn’t make it out of the lab because people are bored by the time they hit the second paragraph!

As we look back from a net-zero future, what do you hope they will say about us?

I hope that 30 years from now someone will write a book just as epic as Daniel Yergin’s ’The Prize’ about the clean energy transition.

Yeah, I know he has a sequel but it’s far too early for one. We’re not even midway through!

🙏 Thanks, Gniewko for taking the time.

I’d love to hear from you, please get in touch and tell me what you’re currently interested in. Here to make friends ✌️