The Energy Security Diet

How to Have a Healthy Energy Mix

Welcome to 8 new readers! If you haven’t subscribed yet, join 115 climate-curious people.

Climate is not a technology problem but a story problem.

Delphi Zero is a consultancy and newsletter about the narrative potential of climate.

By Art Lapinsch

I never cared about politics.

Geopolitics and macroeconomics were always way too abstract for me. Whenever I saw complicated academic figures, my brain would go into standby mode. Too dry, too boring. I had no idea what any of this meant in real-life. Then 2022 happened.

Since the beginning of the year, I have been following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, the global adaptation to the crisis, and the German energy security clown show in particular 🤡

What we are seeing is an evolving case study in poor energy policy. The good thing is we can learn from it in detail. Not in abstract terms but in terms of real consequences for the residents of Germany. I’m one of those residents.

TL;DR: We wouldn’t be here if Germany had a healthy energy mix.

Today, I’ll cover The Energy Security Diet:

Why is the Energy Security Diet important?

How can we evaluate a country’s Energy Security Diet?

What can we learn from the Energy Security Diet?

Let’s do this!

Why is the Energy Security Diet important?

Let’s start with a familiar analogy: Food.

All of us eat and drink to fuel our bodies. Our body metabolizes food and turns it into available energy. This energy allows us to do all sorts of human things like surviving, exercising, working, and so on. Each body is a system.

In Systems Thinking, we speak of stocks and flows. A stock is an element (e.g. my body) and a flow (e.g. the energy from my sandwich) is something that flows through an element. There are inflows (e.g. ingesting the energy) and outflows (e.g. using the energy).

I need a steady supply of energy (i.e. nutrition) to cover my energy demand (i.e. me writing this essay).

Most days, I manage to eat enough to cover my needs but then there are those super busy days where I’m in a rush and I don’t eat enough. Too little food over a long time means that I’m running on a deficit. I will have less energy and will have to rest a lot more. Too little food over an extended period of time means death. We don’t want to be dead.

The goal of our Energy Security Diet is to have an uninterrupted availability of energy at an affordable price.

For humans, we talk about food security. For larger entities like organizations, countries, or continents we talk about energy security. Just like a human body, if a country has too little energy it can’t function properly.

How can we evaluate a country’s Energy Security Diet?

A great primer to evaluating a country’s energy risk is via the 4 A’s of Energy Security:

Availability: Can we find this type of energy on the market?

Accessibility: Can we access and use this type of energy?

Affordability: Can we afford to pay for this type of energy?

Acceptability: Is it socially and politically acceptable to use this type of energy?

Before we dive further into the 4 A’s, it is important to understand that each country has a different energy mix. Think of an energy mix as the nutrients of a diet but for countries.

At the end of the day, each country has to meet its energy demand (i.e. how much energy do we need to keep the lights on). Where this energy comes from can vary significantly. Some countries are primarily powered by renewable energy while others depend heavily on fossil fuels.

The energy mix of a country is a result of its geography, economics, and politics.

Each source of energy has a different technological, economical, and political context. That’s why the 4 A’s should be explored separately for each energy source (oil vs. coal vs. gas vs. hydro…). Each ingredient of your energy security diet should be evaluated separately.

Germany is hungry for gas and as a result, is facing economic and political problems. That’s why Germany is a great case study for energy security 👇

1) Availability 🤷♂️

Question: Can we find this type of energy on the market? If yes, where?

If you are one of the lucky countries that sit right on top of a cookie jar (e.g. Saudi Arabia sitting on oil wells) then you don’t have to think too hard about where to get the good stuff. You have it already and most likely you have so much of it that you can export some of it. Your country is a net exporter.

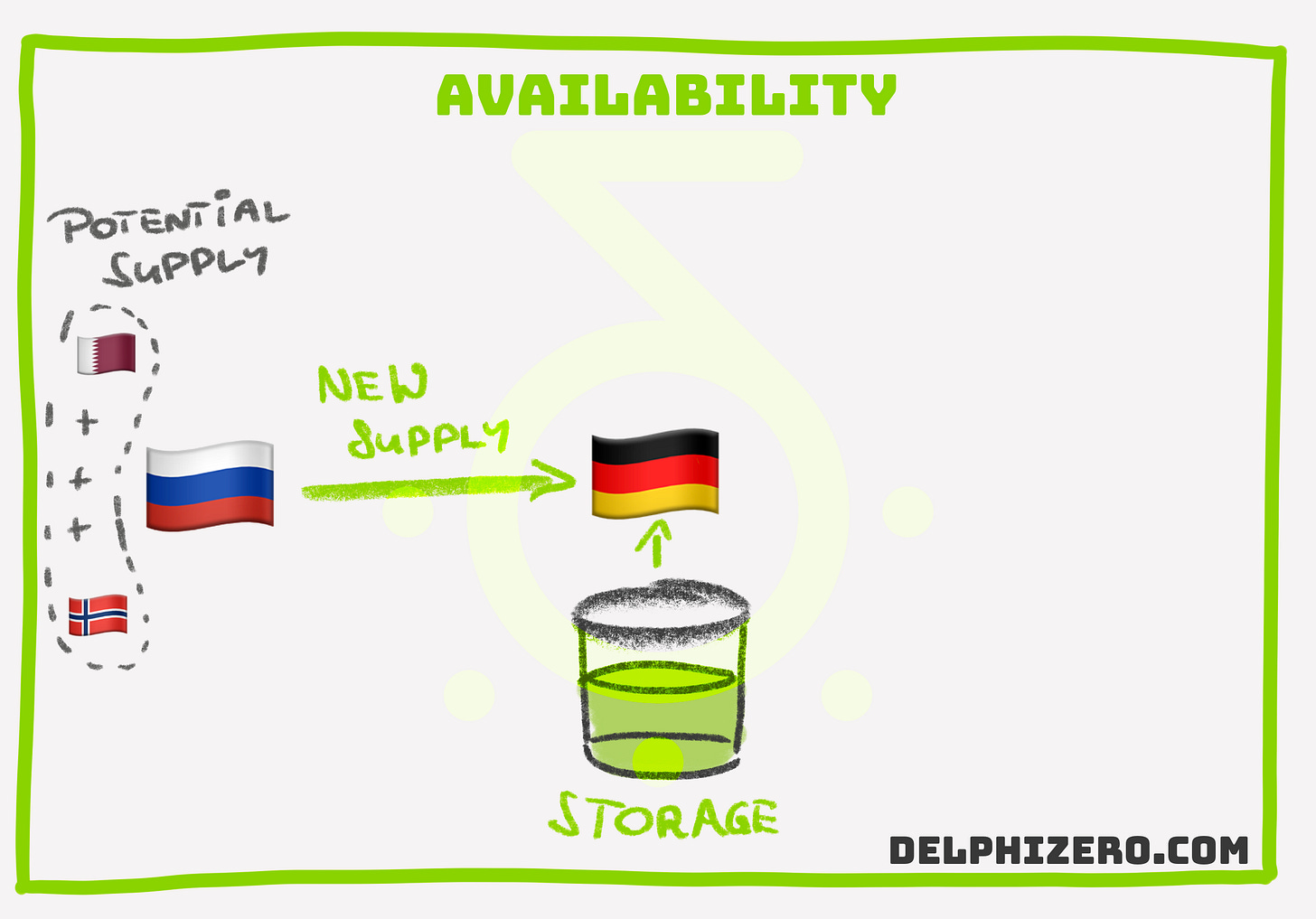

When it comes to natural gas, Germany is not so lucky. That’s why it has to import natural gas from the global markets. So if you open your peepers and analyze the world market you’ll see that your top 3 options are Russia, Qatar, and Norway. Germany is a net importer.

It is important to note that being a net exporter and net importer can change with the energy type. You can be a net exporter of coal but a net importer of oil.

Availability should be also broken down into new/incoming supply and stored supply. Think of it as going to the supermarket for food (i.e. import) vs. opening your own fridge (i.e. storage).

Lesson learned: Have stable sources regardless of whether they are external or internal.

2) Accessibility ✅

Question: Can we access and use this type of energy?

In simple terms we can distinguish between two types of accessibility:

Political: Is the supplier willing to export their energy to the buyer?

Technical: Do we have the technical infrastructure to transfer the energy from the supplier (Russia, USA, own storage) to the buyer (Germany)?

A political limitation means that your supplier does not want to send you energy because of a kerfuffle that you might have. Imagine going to the supermarket and the vendor says no because you don’t like his haircut. Same same but on a geopolitical stage.

We are currently seeing such a political limitation in the context of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. Germany - as part of the EU - is participating in strong economic sanctions against Russia. Moreover, Germany is supplying Ukraine with heavy weapons for their fight against Russia.

In response to that, Russia is trying to force Europe’s hand to remove sanctions and stop helping Ukraine. They try it by cutting the natural gas supply to 20% of its normal capacity. The cookie is mad.

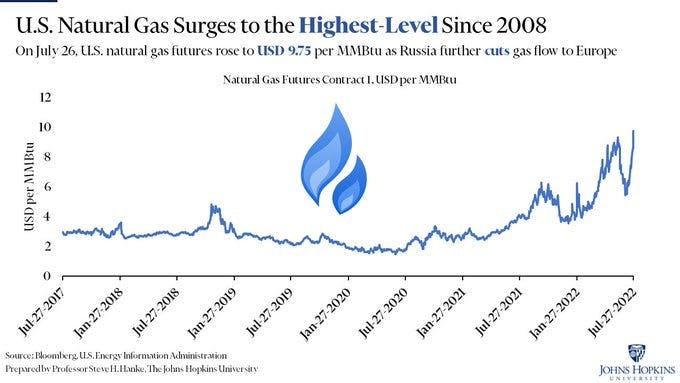

#EconWatch: As Russia slashed gas flow to Europe via the Nord Stream 1 pipeline to 20% capacity this week, US natural gas futures prices hit their highest level since 2008. Thanks to sanctions on Russia, the EU will face a long, expensive winter.

A technical limitation means when there are physical barriers to receiving the energy. You want to have your snack delivered to your home but the street leading to your home is flooded.

For the coming explanation, it helps to dive a bit deeper into natural gas. Due to its physical properties, there are primarily two ways of transporting natural gas from point A (supplier) to point B (buyer):

Pipeline: Gas is pumped through a pipeline network above or below ground. Due to the complexity of construction, cooling, and operation, these pipeline networks are regional. You have pipelines that span across an entire continent but you don’t have a pipeline network that connects across the largest oceans. Your supply is regionally constrained.

Liquified Natural Gas (LNG): There is a process by which natural gas can be turned into a liquid for transport on massive cargo ships. LNG has the advantage that it can be shipped across an ocean. Suddenly, Germany can theoretically get gas from the US… but the process is expensive and both countries (exporter and importer) need LNG terminals to liquefy and gasify the natural gas respectively.

The kicker is that Germany does not have such LNG terminals (yet).

On top, one of the largest LNG plants in the US had a “technical malfunction” just as Europe wanted to start sourcing more gas from countries like the US. This thread below offers a fascinating read 👇

Freeport, one of the largest US plants exporting liquefied natural gas, exploded on Wednesday.

Freeport represents a critical piece of infrastructure in Europe's divestment from Russian oil. Yet this story is almost no where in the mainsteam news, so let's dig in.

And just for good measure, I want to address the topic of national storage facilities. Think of them as your pantry or your fridge.

Gas storages are an important factor in energy security. Countries store their surplus energy in summer for colder months in winter. One such gas storage facility is Rehden, Germany - one of Europe’s largest storage facilities with 4 billion cubic meters in capacity. This storage capacity equals half a month of all of Germany’s gas usage (industrial; residential; etc.).

The juicy part here is that in 2014 Germany’s government allowed Gazprom to buy this gas storage facility. The assumption was that Gazprom - a Russian state-owned company - will fill the gas storage in a similar way as a German operator would. Well, turns out that Gazprom used Rehden as another piece on the political chessboard by keeping the storage at 0.6% of capacity until the time of Russia’s invasion. It was practically empty.

This is an interesting example since it mixes political limitations with technical limitations. Technically, Germany can’t access the energy because the storage is physically empty but the root cause was a political play.

Lesson learned: Accessibility of your energy is key.

3) Affordability 💶

Question: Can we afford to pay for this type of energy?

Affordability is as key in your restaurant choices as it is in your energy purchases. You risk running out of money if you live at large.

The question everyone should be asking: Do we expect energy prices for a particular source of energy to go up or down?

I’ll leave you with two ideas:

Fossil Fuels Are a Scarce Resource: There is a finite supply of fossil fuels. The less we have of it the more expensive it becomes.

Renewable Energy Is a Technology: There is an infinite supply of renewable energy (wind & solar). The more we produce of it the cheaper the underlying technology becomes.

Ramez Naam put it best when he said:

“Clean energy is a technology, not a raw material. Its long-term price isn’t so much dictated by the law of supply and demand as it is driven by the virtuous cycle of increased demand leading to reduction of cost via Wright’s Law / the learning curve, and those lower prices leading to increased demand. And that’s a global phenomenon. Deploying more clean energy technology in Europe makes clean energy cheaper in the US, in China, in India, in Africa, and everywhere.”

Since Germany still depends on natural gas for ~15% of its electricity production it is currently experiencing a crazy price hike in electricity prices. This is a massive security risk.

BREAKING: Germany 1-year forward baseload electricity surges >€400 per MWh for the first time ever.

We are truly into crunching territory for the country's energy-intensive manufacturing industry.

The current price is ~1,000% higher than the €41.1 per MWh 2010-2020 average.

As I wrote last week:

Price Explosions: The supply-reduction results in rising costs of natural gas and an explosion in electricity prices. Utility providers usually have their contracts locked in for one- or two-year periods. If there’s a sudden price increase there are two scenarios that are bad: (1) utility providers bear the financial loss and run the risk of becoming insolvent, or (2) price increases are being passed onto the consumers and you risk accelerated inflation. Both cases are no bueno. Governments in France and Germany are currently preparing to nationalize major utility providers.

Lesson learned: Don’t forget about the potential price swings of your energy source.

4) Acceptability ☺️

Question: Is it socially and politically acceptable to use this type of energy?

Imagine going to a steak restaurant just to remember that you are actually vegan. It’s unacceptable for you to eat any animal protein, that’s why you just order the french fries and ask which oil has been used for frying. You hope it’s the vegetable one.

Similarly, social and political acceptability plays a huge role in a country’s decision about its energy mix. Germany is a prime example where decades of public discourse have led to a negative stance toward nuclear power. Germany’s political leadership reacted and since the early 2010s has been dismantling its nuclear fleet down to three remaining power plants.

Nuclear power is predictable and carbon-neutral. It could have helped Germany to withstand the current reduction in Russian gas supplies. The problem is that over the past decades this type of energy was socially and hence politically unacceptable. Oops.

Now there’s a shift in public opinion and due to the energy crisis, there’s a revived discussion about runtime extensions for the three remaining power plants and a recommissioning of three further power plants, which have been taken offline just last year.

Lesson learned: Public opinion can have a huge impact on energy security.

What can we learn from the Energy Security Diet?

Germany’s energy security diet is unhealthy.

30% of Germany’s primary energy consumption is met by fossil fuel imports from Russia. Germany has an over-reliance on cheap and bad energy from the East.

Germany, it’s time to go on a healthier Energy Security Diet.

Dear reader, if you want to discuss climate (questions; topics; jobs; opportunities; etc.), please reach out to me.

Also, if you enjoyed this walkthrough, I’d appreciate it if you could share it with people who might find this interesting. Thank you 🙏

I’m looking forward to hearing from you,

Art

The original of this story appeared first on Delphi Zero.