Spotlight on Infrastructure

An in-depth convo with Jarek Khoilian who traded Hollywood spotlights for infrastructure insights.

👋 こんにちは to 2,296 climate buddies 🌳

Climate is not a technology problem but a story problem.

Delphi Zero is a consultancy and newsletter about the narrative potential of climate.

Have you ever asked yourself how massive infrastructure projects get built?

Well, today is your lucky day! I interviewed my buddy Jarek who lives and breathes all things infra. We covered:

🎥 Why he switched from a career in Hollywood to infrastructure investing

🏗️ How large infrastructure projects get built

🌞 What infrastructure insights make him optimistic about our net-zero future

Aaaaaaand, Action!

Spotlight on Infrastructure

By Art Lapinsch

Jarek, before we dive into energy & infrastructure, you have to tell us about your time in Hollywood.

That's always been a fun icebreaker with people! It even caught the attention of my now-wife, who found it surprising that I went from entertainment to finance - especially infrastructure.

After high school, I was unsure of my career path. My father, a software engineer, sparked my interest in technology, so I enrolled in computer science at the nearest big university. However, after two months, a failed (or so I thought) calculus exam convinced me to switch gears.

Throughout high school, I had been running live sound and doing event production with a friend. We loved working on concerts and theater, and film seemed like a natural next step. Having made terrible shot-for-shot recreations as a kid, I craved a return to Los Angeles. We packed up, found an apartment, and within our first week, met a family friend who was working as a commercial producer.

She explained the need for experience and the reality that we couldn't get hired without it. Realizing we were in over our heads, we started applying everywhere – Craigslist, Facebook groups, and random production job boards. Our first break came with a non-paying production assistant gig on a movie about the Haitian earthquake. This shoot was our film school – walkie-talkie etiquette, coffee runs, and the crucial skill of double-checking burger orders. Over the next three months, we fought our way onto student shoots, random TV shows, and indie films.

Eventually, we landed gigs on a couple of Enrique Iglesias music videos, which included the now-famous story of driving him and the producers around LA. After a year and a half on various shows, a studio executive offered some unexpected advice:

"You've come far, but should really consider taking the time to go back to school."

On a whim, I did just that.

I contacted the university I dropped out of two years prior, and luckily, they welcomed me back. After another year, I transferred to USC in LA, where I delved into finance while still working at the studios. Ironically, it would be a lost phone that would lead to my first job in NYC doing municipal bond insurance, which kickstarted my career in infrastructure.

What a story! Now, let’s dive into infrastructure. What is municipal bond insurance? And what was surprising about that industry?

My infrastructure journey was definitely a winding road, but each stop felt like a step closer to where I wanted to be.

That first job out of college - municipal bond insurance - seems pretty far removed from the world of infrastructure, but it turns out it was a great launching pad and got me from LA to NYC.

In the US, most infrastructure projects are funded by states and localities issuing debt - these are municipal bonds. They're not funded directly out of budgets like in some other countries, but bought by investors – they were even advertised on talk radio! The credit rating of the issuer - the firms building the infrastructure - determines the interest rate on the bond. Well, after the 2008 financial crisis, those ratings took a beating, which meant these projects were suddenly way more expensive if they could even attract investor interest at all. That's where municipal bond insurance comes in.

Basically, we guaranteed repayment to investors, lowering the risk and the interest rate for the issuer. We took a cut, but they saved a ton of money over the long haul. This role was fascinating – I saw tons of different credit profiles, which gave me a real feel for the intricacies of how infrastructure gets funded in the US.

Two years in, I happened to be reading the bond documents for some projects in NYC, including the redevelopment of LaGuardia Airport in NYC – long considered one of the worst airports in the country.

Through a bit of networking and a lot of self-study, I snagged a role with a private equity firm that was financing and managing the project. This was a huge shift, way closer to the actual building of infrastructure. It was like being a lawyer, financier, and construction manager all at once.

We focused on public-private partnerships, or PPPs, which are considered a mixed bag these days. The idea is to involve private financing in building new infrastructure like toll roads, airports, and even social buildings like hospitals to reduce the risk on the public sector. Different teams of construction companies, operators, and investors would compete for these projects, and as the equity partner, I was the lead negotiator, dealing with everything from legalese to the nitty-gritty of the project itself.

Honestly, the biggest challenge wasn't the financing – it was convincing all these engineers and project managers that I knew what I was doing, even though I'd never set foot on a construction site!

After a few years, I felt this itch again, a sense that I wasn't quite there yet. I realized that I was spending more and more of my time focused on arguing amongst my consortium members on projects that I felt had limited impact. One of the largest Canadian investment banks specializing in infrastructure had been an advisor to us for many years and I had developed a strong rapport with the team. When an opportunity came up to join, I took it immediately.

It was intense – running models til 6AM was par for the course - working on massive deals at major US ports, large rail lines, and even cell towers in subway lines. This was finally the kind of work I'd envisioned, though ideally on the investing side, not the banking or advisory side. The plan was to build my network and really sharpen my skills for a couple of years, but life isn't always as straightforward, right?

In a bit of a crazy move, I jokingly applied for a venture capital role in Tokyo, a city that had always been a dream of mine (because of the trains). A few months later, my wife and I were packing up our NYC apartment for a move across the globe.

Tell us more about your train obsession. Why are they special to you?

It's hard to pinpoint exactly when love affair with trains began.

As a kid, Thomas the Tank Engine and train engineer costumes for halloween were my jam. But as I grew older, two things really fueled the obsession.

First, there's always been this fascination with cities and how people interact with them, especially how they move around. The way people navigate a city is like a living organism to me. Second, there's this romantic notion of the scenery rolling by as you're whisked away to a new destination.

These two ideas coalesced into the idea that trains represent freedom of movement and connection, the lifeblood of a city. I know it's cheesy, but I still love standing on a platform, watching people and wondering where their journeys are taking them. Plus, there's still that little kid in me who just loves big machinery.

Having lived and worked in the US and Japan, what differences have you noticed? What's different in the professional world? What's different from an infrastructure perspective?

The saying "living somewhere is vastly different from visiting somewhere" has never been truer than with working in Japan. In my current role with a traditional manufacturer, I have strived to understand some of the many cultural nuances that comes with working for a Japanese company. Coming from my experience of working and living in the US, I recognize that I may bring a set of expectations, behaviors, and potentially even biases and subsequently, I have learned to recalibrate my barometer for working life in Tokyo.

I'd argue one of the largest differences is the risk appetite exhibited by large corporates across both countries. From my perspective, it seems like it takes longer for more traditional Japanese companies to warm up to the idea of new business ventures, particularly if there isn’t a “guaranteed” outcome. Where this comes from is hard to pinpoint but Richard Koo’s book “The Holy Grail of Economics” suggests this risk-off mentality might be a long-term effect of the 1980s bubble burst and the subsequent lost decades. As you can imagine, this can be particularly frustrating in venture capital for infrastructure and climate tech – these are big, complex challenges that require taking calculated risks over a long time horizon.

Another difference, and a rather challenging one for me personally, is the sheer number of meetings. It is common practice to hold meetings to discuss upcoming meetings, supposedly to ensure everyone is informed about potential investments and to front run questions. But often, it's just people reading aloud what was already sent beforehand. For complex financings, this unnecessarily in my opinion, elongates the main meeting by reiterating previous discussions, making it challenging to discuss the bigger picture.

Specifically regarding infrastructure, what can the US learn from Japan? What can Japan learn from the US?

Japan's infrastructure is a big reason I came here. It's a stark contrast to the US approach.

Here, the Ministry of Land, Infrastructure, Transport and Tourism (MLIT) has deep expertise in both procuring infrastructure and understanding its impact on larger systems. They're supported by a network of quasi-public companies like the Japan Rail entities that are publicly floated but with the government holding a large percentage of shares. This combined expertise allows the government to effectively manage project costs and design, while accurately assessing private sector involvement without needing to rely on expensive external consultants like in the US.

Part of this success comes from a more centralized approach, where regional and national concerns are considered together, avoiding the short-term political wrangling common in the US. Here, projects are often chosen based on feasibility and smooth delivery, not just the lowest possible cost. In the US, the focus is often on the lowest upfront cost, regardless of long-term issues and budget-busting change orders and contingency allocations that plague North American infrastructure projects.

Finally, Japan has a more streamlined land acquisition process compared to the US. Property owners can't endlessly stall projects with lawsuits, which delays projects and adds massive costs in the US. A good example of this is the Purple Line project in Maryland that has the added benefit of a judge who is personally impacted by the project. While Japanese culture does emphasize consensus building, it's the legal and technical systems that truly facilitate smoother infrastructure projects.

On the flip side, I would honestly be hard pressed to think about what to bring back from the US to Japan in its current state.

People know that infrastructure projects are important. But what are a few things that are under-appreciated about building new infrastructure? What's surprisingly difficult and what's your best guess on how to solve it?

For the average person, there's one major challenge that's invisible: Utility Relocations.

Imagine a maze of underground utilities beneath our streets: fiber optics, water, sewer, electrical lines, and more. Any new construction disrupts these, requiring relocation. Making the problem worse is each cable and pipe likely has a different owner. As the project owner, you must convince each utility company, at your own expense, to move their assets on their own timetable, regardless of delays or cost increases to your project. This is particularly true for large-scale horizontal construction projects (roads, railways) in built-up environments.

For example, when we were considering a light rail project near Toronto, we faced 12 separate utilities, each with their own approval process. Additionally, the project would have required shutting down two oil pipelines that would cost hundreds of thousands of dollars per day.

Ideally, the public agency coordinating the project could force utilities to operate on stricter schedules and provide up-to-date asset location documentation. The solution likely lies in better contract design to incentivize timely cooperation but unfortunately, declining institutional capacity in North American agencies often hinders such expertise including the ability to get these enabling works done ahead of project procurement.

From your perspective, which types of infrastructure projects are currently over-discussed? Which ones are under-discussed? Why?

This is always going to depend on location but in the US, there's an overemphasis on roads, particularly our un-tolled highway system. While reflecting American development patterns, this is clear when comparing federal and state funding for highways versus public transportation.

Reflecting the material conditions on the ground however, it actually becomes hard to argue that many forms of infrastructure are under-discussed given there's such an extreme deficit of investment, roughly $50 trillion by 2030 per the Institute of Sustainable Development, to get us on a path towards net zero.

One could additionally argue that certain renewables, such as wind and solar, whose supply chains are relatively complex and are beginning to be constrained due to geopolitics have garnered outsized attention given the maturity of the technology and their common perception as the only forms of clean energy. On the other hand, nuclear power, a near-fully renewable energy source, is rarely discussed due to outdated safety concerns and political opposition

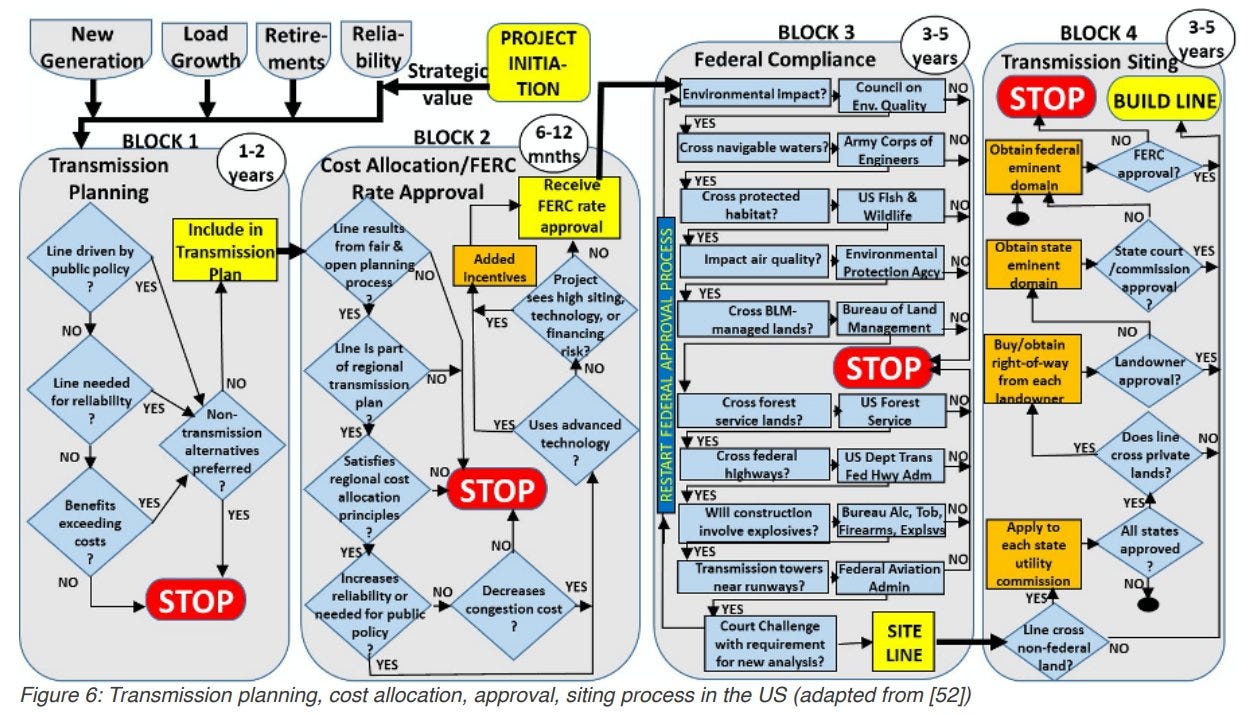

A truly under-discussed area of energy infrastructure is transmission. Utilities don't want to spend the capital on expensive, non-revenue generating assets, they're incredibly complex to build due to regulatory and right-of-way acquisitions, and requires the coordination of a multitude of stakeholders such as the various grid operators in each region of the US. Currently, there's roughly 8,000+ renewable projects representing roughly 1,000 gigawatts worth of capacity, just slightly lower than the existing grid, that are awaiting transmission projects to actually hook them up to the grid.

The large transmission lines are only one part of the problem however, transformers and other utility-scale electrical components that enable all this energy to actually be utilized by people and businesses have been in short supply for nearly three years per the ISM manufacturing survey.

Until these sort of development and supply chain issues are resolved, transmission is going to be both under-discussed and underfunded.

Which types of infrastructure projects excite you in regards to our climate goals? What will get us to net zero?

A global shift towards renewables, especially in regions like China and India where coal dominates the energy mix, will significantly move the needle.

Developed nations should increase funding to help developing countries implement these projects faster as well, eliminating their reliance on fossil fuels before energy demand surges.

Additionally, many cities are adopting climate-friendly policies like public transit expansion and bike lanes that not only reduce greenhouse emissions but also eliminate local pollutants like noise and tire dust, which even electric vehicles can exacerbate. Overall though, the transition to electric vehicles and charging infrastructure buildout is a net positive, particularly in car-centric cities like Los Angeles that are slowly transitioning towards multimodal transportation. However, the environmental impact of battery manufacturing cannot be understated and often is less visible given the geographies it occurs in.

Focusing on energy production and road transportation – the largest emitters – can reduce overall emissions by roughly 50%, with the technology potentially impacting other downstream sectors like manufacturing, agriculture, and construction.

The ultimate game-changer for net zero could be fusion energy. After speaking to a number of companies in the space like Kyoto Fusioneering and OpenStar, I've gotten a lot more optimistic.

What in the world of infrastructure makes you optimistic about net zero?

There's a number of things to be optimistic about!

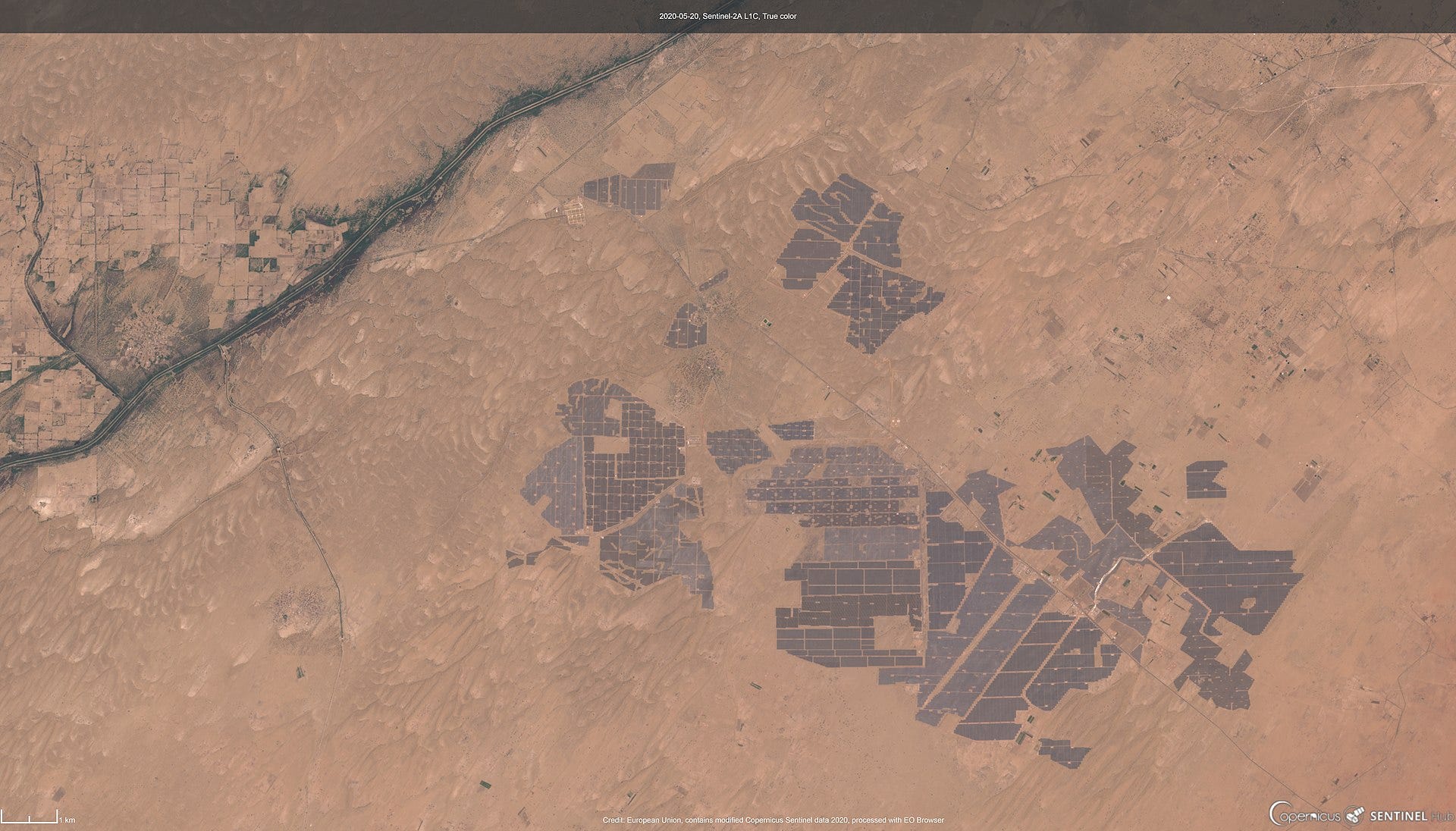

As mentioned, while there's challenges in actually getting the energy to the end user, there's thousands of renewable projects coming online globally, including a number of large scale wind and solar projects like Vineyard Wind 1 in the US and further construction on the Bhadla Solar Park in India.

We're also seeing large utility scale battery projects like the 300 megawatt Victorian Big Battery in Australia and 3 gigawatt storage at the Edwards-Sanborn Solar and Storage Project in California, both that will go a long way in mitigating the "duck curve" issue with renewables.

While I'd love to see more transit projects coming online, we've got the Purple Line Extension in Los Angeles opening over the next few years and the amount of battery electric buses I saw in China recently was incredible. We've also seen a number of countries pass the "tipping point" of 5% market adoption for EVs that'll spur an even greater level of investment in charging infrastructure.

On a completely anecdotal note, it's just good to see how engaged people have become around these topics and recognizing that there's no time like now to start meeting net zero goals before it's truly too late.

Ok, one last one, I promise… What can infrastructure learn from Hollywood?

Probably the hardest question you’ve asked!

These are such disparate worlds that you’d be hard pressed to think of any crossover lessons. But I think one of the ways the industry and projects suffer is their marketing. They often lack an ability to communicate the long lasting benefits to the public.

By taking a storytelling approach, government agencies and owners can take an excessively technical project and weave a narrative that the people who stand to benefit the most can actually understand.

🙏 Thanks, Jarek for taking time and sharing your perspective.

I’d love to hear from you, please get in touch and tell me whom I should interview next or which topics you’d like to see covered ✌️